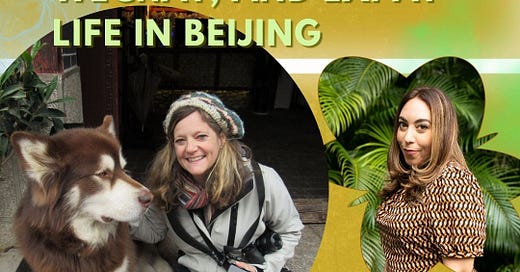

Part 1: An American Expat in China with Melanie Duhon

Pandemic life in Beijing, The Brickening, WeChat, Bird-Walking, and More

I recently spoke with American expat and trailing spouse, Melanie Duhon about her many years living in Beijing, including her time during the Covid-19 pandemic and her experience of WeChat and “The Brickening.”

This was a lengthy discussion, so I divided the written, edited version into two parts. In Part 1, here, we cover:

The Beijing Lifestyle

“The Brickening”

Learning Chinese

WeChat

The Surveillance State

The Beijing Pandemic Experience

And in Part 2, we discuss:

Pop Culture

Racism

Travel

Hugging Pandas

Food

Collective vs Individual Culture

US and China Relations

I’ll share Part 2 soon.

** For the full, unedited interview check out the audio and video here.

I honestly could have spoken with Melanie for hours! She’s lived a life that few of us will ever have the chance to experience. This interview made me nostalgic for the positive elements of life abroad and the way expat women often form close-knit, unique, and meaningful communities.

A note from me:

This interview may contain something you find upsetting or controversial. I’m here to listen and learn from my guests. Take what you need and leave the rest—is my attitude.

China itself is a fraught topic in the US and the more we can listen and learn, the better.

I’m grateful I could speak with Melanie because many Americans currently in China aren’t allowed to talk about their experience or don’t feel safe doing so. The first person I wanted to interview wasn’t actually able to speak with me, as their employer forbid it.

I would love to visit Beijing myself, but I worry that my status as a former U.S. Diplomat would complicate my trip. However, I find the country and topic fascinating and I hope you do too. If there are experts on China-related topics that you’d like me to interview in the future, let me know in the comments or shoot me an email.

I obviously don’t support any form of genocide.

Enjoy!

These interviews always release first on Youtube, and you can take advantage of that by subscribing to my Youtube channel and turning on the notification bell if you’re active on that platform.

*This interview was edited by me for readability.

Melanie Duhon, an American in China

Introduction:

Charlotte: Melanie, welcome!

Melanie:

I'm delighted to be here. Thank you for having me. My name is Melanie Duhon. I am an American who has recently returned from living in Beijing, China for the second time. My husband works for a Chinese company, which led us to live there twice, first between 2011 to 2014, and then again from August 2019 to just recently. So we had the entire COVID-19 experience in China, which was significantly different from the situation in the United States.

My background is in biology, but I’ve been teaching English as a second language and participating in volunteer activities. While in China, I enjoyed immersing myself in the culture, interacting with people from around the world, and having a great time.

Trailing Spouse?

Melanie: I am what they call a "trailing spouse." Being a trailing spouse can either be the best or the worst thing in the world. Personally, I love it. When you work abroad, you don't get to fully enjoy the country as much as you would like because of work obligations. Trailing spouses, on the other hand, have the opportunity to really explore the country, from visiting local markets to trying different lunch spots.

The main downside of being a trailing spouse is not having a job, which can be an adjustment for someone like me who has been working for most of my life. However, in China, it's difficult to obtain a work permit. Most of my friend circle were also trailing spouses, so we had a decent community of mostly expat women, but some husbands as well. We formed friendships and engaged in various activities together, such as traveling, playing Mahjong, and attending history lectures with a local historian.

Despite not working, I had the opportunity to socialize and connect with people from all over the world, which made the experience in Beijing truly awesome.

Housing?

In terms of housing, we lived in the downtown area of Beijing. Beijing is a massive city, and most of my friends resided within a 10-mile radius on the eastern side. Some apartment complexes catered more towards expats and had amenities like ovens, which are not commonly found in Chinese apartments. The layout of these apartments was also slightly different, and some had wood floors instead of stone floors.

Many of us lived in close proximity to each other. While my compound wasn't exclusively foreign, it had a higher concentration of foreigners compared to most compounds. It consisted of five buildings, and my apartment was located on the 21st floor of a 35-floor building. I was fortunate that my company covered the expenses, and I enjoyed a beautiful view of downtown Beijing and the nearby Chaoyang Park, which could be considered similar to Central Park, but with its own unique charm.

However, I had friends who chose to live in the suburbs, particularly those with younger children. Living in the suburbs offered the advantage of having a yard and being closer to good international schools. During the first two years when my son was with us, he had to take a half-hour bus ride to school, but the commute was relatively smooth due to less traffic during the pandemic.

Our complex remained the same throughout both of our stays in Beijing. We initially lived there when our children were eight and eleven years old. Then later returned when they were older. The complex had a spacious yard and a shared area with a playground, swings, and trampolines. The kids absolutely loved it, so it worked well for us.

Cost of Living?

Charlotte: How is the cost of living in general? How much is a nice apartment in Beijing? Can Americans even go live there? Do you have to have a work permit kind of situation?

Melanie:

They've reinstated the tourist visa, but you only get 90 days on a tourist visa. To live there, you have to have an employer who has sponsored your work permit or be related to someone who does.

Beijing is expensive to live in, especially the apartment part. We could never have done that without my husband's company paying for the apartment. Our apartment was about $5,000 a month, and while it wasn't huge, it had a great view.

However, you can live cheaper if you live outside of town. Teachers do it, and there are a lot of Westerners who go and teach in China, and sometimes their housing is paid for. But even then, the apartments are expensive.

Starbucks coffee and anything Western is expensive, but if you just want to make yourself some noodles, or go down and get an awesome meal, it can be cheap. Just behind my apartment complex, we still had some old hutong areas. I could get a donkey meat sandwich for like a dollar and a half. I could get some bao buns for pennies. There was a fresh noodle guy, and I could get a pound of fresh noodles for a dollar. It always blew me away how cheap it was.

Oh, and about the donkey meat sandwich, it tastes like corned beef.

No Ovens?

Charlotte:

I'm curious if Chinese apartments have an alternative to ovens or if baking is just not popular there?

Melanie:

Generally, people in China don't bake much at home. Some apartments might have toaster ovens, but in general, most Chinese apartments don't have ovens. They prefer to cook fresh food and buy baked goods from stores.

However, there are places where you can go and pay to use ovens, similar to how you can paint pottery or do sip-and-paint activities. So, for special occasions, friends may gather to bake their own birthday cakes.

Big City Living?

Living in a city of 22 million people is an interesting experience. If you avoid rush hour, it's fine. Public transportation in China is exceptional, with buses, subways, shared bikes, and affordable ride-sharing services like DD (similar to Uber). During non-pandemic times, the subways and buses can get crowded, especially during peak hours.

However, I personally enjoyed city life. It was a bit of a shock initially, as I had been accustomed to living in the suburbs, but I grew to love it. I enjoyed the convenience of having stores nearby, visiting wet markets for groceries, walking to meet friends, and strolling through the park. Park life in China is fantastic, particularly for the older generation. They spend a lot of time in parks, engaging in activities like dancing, Tai Chi, playing badminton, and walking their pet birds.

Walk Their Birds?

Yes, you heard that right, they walk their birds. Let me explain. The older generation in China spends a significant amount of their time in parks and they keep songbirds as pets, so they have a daily routine of visiting the park with their birds. They bring their little birds in cages and swing them. I'm not sure why they do this, but it's a common practice.

Then, they gather in a designated area where they hang their bird cages on trees. They spend time chatting and socializing, much like retired people do. It's one of the many enjoyable traditions of the older generation in China that create a strong sense of community.

I find it amazing, and I wish we had something similar in our country. It would be fun to grow old in such a way. It's a completely different experience of aging from the U.S. way.

Does Beijing remind you of anywhere else?

It's somewhat comparable to nothing in America, absolutely nothing. Ha ha. Maybe a little bit of Tokyo, but Tokyo is a little less... I'm struggling to find the word to describe it. There are more rules and etiquette in Japan, while China is a bit looser and a little dirtier, which I actually kind of like. I can compare Beijing to many other Chinese cities, but it's difficult to find a comparison outside of China.

Charlotte:

Is it super clean like Tokyo, where the subway is so clean you could eat off the floor?

Melanie:

No, Beijing is not like that. It has improved significantly over the past 10 years. In fact, when we left in 2014 and returned in 2019, it had gotten a lot cleaner. In 2014, I would never have used the public bathrooms. You could smell them as you walked by and knew a bathroom was nearby. But when we got back in 2019, they were all very clean. I had no problem using them, even though they were squatty potties. It has definitely become much better, with many things being cleaned up.

The Brickening

The process of cleaning things up has its pluses and minuses. We like things to be clean and efficient, but they're also getting rid of a lot of fun, cultural stuff in the process.

Beijing is known for its hutongs, which are narrow alleyways. I think they were built by the Mongols, and they consist of courtyard homes with narrow alleys between them. They were squares of courtyard houses, with open space and buildings. Over the centuries, they have been subdivided and passed down through generations, leading to overcrowding. Some people even operated stores out of the front windows, where you could climb up and buy something. The walls along the alleyway would be filled with signs for restaurants and other establishments. However, many of these old structures have been demolished or renovated, losing some of their original charm and history.

They call it "The Brickening" when they wall up the fronts of the hutongs to prevent people from running their businesses. This has taken away some of the charm of the area, as seen in old or newer pictures of Beijing with their red lanterns and gray stone paths. These hutongs are lovely to bike and walk through, and they have been home to communities for generations. However, they are now being broken up, with people being relocated to new apartment complexes outside of town. This has disrupted the sense of community, and while some are happy with their new apartments, others miss their old community.

The Brickening is happening because there were too many people living in the hutongs and too many unregulated businesses. It is a tourist area, and they want it to be nicer. These places don't have their own bathrooms, so the community bathrooms were under stress due to the high population density. It was like trying to fit more and more people into an apartment complex with only one floor. While reducing the population is better for health and safety, it also affects the cultural experience of Beijing's hutongs.

Historical Study Group

A historical study group I joined was focused on the history of modern China, which started in the 1600s. When COVID happened and international students were sent home, a historian who had been doing walks and talks approached our active group of women and offered to do a lecture series.

Initially, it was supposed to be six or seven lectures, but we enjoyed it so much that it continued. We met every other week in one of our homes to learn about different aspects of Chinese history. The American historian, being fluent in Chinese and married to a Chinese woman, provided a unique perspective. It was a great experience for me since I don't speak Chinese well and having someone who could explain things happening around me was valuable. We had discussions, readings, and enjoyed the intellectual engagement, especially since most of us were not working and wanted something beyond lunches and socializing.

Learning Chinese

Charlotte: It blew my mind when I found out that it takes two years to reach level two in Chinese, whereas I reached level two in French in just four weeks of studying through the FSI system.

And level two is not even an adequate level; it's more like the beginning of your language journey. Knowing that would make me hesitant to try to learn Chinese because of how challenging it is. It would take years and years of full-time study to become fluent.

So, how was the overall language barrier while living in China as an American?

Melanie:

Learning Chinese was much more challenging compared to learning French in high school. French has cognates, which are words similar to English, making it easier to recognize and understand. But Chinese is completely different. The written language consists of characters, which are not helpful for beginners. And then there's the issue of tones. For example, the word "ma" can have multiple meanings depending on the tone, making it difficult to grasp for non-native speakers. If you know five words, you probably know 40 once you add the tones.

As a white American, the language barrier was not a major issue for me because people didn't expect me to speak Chinese. People were generally very patient with me and had low expectations when it came to my Chinese language skills. They would often get excited even if I could speak a little bit. So, that was a positive aspect.

In fact, I reached a point where I spoke enough Chinese that people assumed I was fluent, which caused some confusion. My biggest struggle was understanding what others were saying to me. I could express my needs and wants in Chinese, but comprehending spoken Chinese was very difficult. I believe this issue stems from a lack of emphasis on listening and speaking in the Chinese language learning system.

In my experience, the focus was more on vocabulary and grammar, with limited opportunities for conversation and listening practice. I tried various Chinese classes and invested a significant amount of time, but I eventually gave up when the pandemic hit because online one-on-one classes weren't as effective for me. I prefer learning languages in a group setting where I can learn from others' mistakes as well. The pandemic made that impossible, so I halted my language-learning journey around level three.

My daughters, on the other hand, became fluent in Chinese. One of them spent a year in China during high school and attended a Chinese high school, while my son lived in China for a total of five years. They had the advantage of being young, and their language skills improved over time.

However, I've witnessed a double standard for Chinese Americans who may look Chinese but can’t speak the language. For example, a friend of mine who is Chinese American had to face questions from Chinese locals about why her children, who look Chinese, don't speak Chinese.

Fortunately, in China, everyone uses their phones for everything, including translation apps. While not many people speak English, they understand that I speak English and will make an effort to communicate.

WeChat

Charlotte: Speaking of phones and apps, how is WeChat?

Melanie:

WeChat does almost everything. It’s amazing and it's awesome, it's great, but the reason it's amazing, awesome, and great is because everybody is on it. Everybody in China has a WeChat account, and everybody uses it for everything.

You don't have to say, "Okay, I want to get in touch with Sally," Okay, she is on Facebook with me, so I have to Facebook message her, but you know, but I want to get in touch with Sam, okay, I text Sam. You know, everybody's on a different platform here, right?

But, it's a monopoly, and it's controlled by the government. It is completely watched. There are words you cannot say in WeChat.

As for the internet experience, there is some truth to the stereotype that certain websites and online content are restricted in China. The internet is subject to censorship, and some websites or platforms that are commonly used in other countries may not be accessible or may have limited functionality in China. However, there are alternative Chinese apps and platforms that serve similar purposes and are widely used by the local population.

One of the things everybody has, all expats have in China, is a VPN, a virtual private network, which you put that sucker on and tell it you're in LA, and then you can get on Facebook and all of those things that are blocked. It is not difficult in China at all to do that. It is very easy to get VPNs.

Chinese people do it as well, but they are against the law now. So, if you talk about it on WeChat, if you talk about, "Oh, turn your VPN on because you want to go to this site," then that will get flagged, and somebody will look at it, and if it happens enough on your chat, your chat will get deleted. So, yeah, the government is watching.

So we called it various things, like very precious necklace, or your Veep. There were a whole bunch of different things people called it, but you didn't say VPN.

WeChat also lets you make groups of people. So, for instance, with your Charlotte's Lagoon, you could have a group of your followers all in this chat, and you would use that to promote yourself and tell people when you had new episodes out or things like that. But at the same time, you could individually talk to each of those people, and those people could have that but not have it turned on all the time, so that they could look at it whenever they want. There is no app like that in the U.S.

It's a very, very flexible way to market things, and to contact groups of people too, like if you go out for lunch with people. Wechat then could split the lunch bill very easily. Everybody's paying on WeChat anyway and you can send money back and forth, like Zelle.

Plus, you can use it like Facebook too and post pictures. I didn't really do that, but a lot of people do, so it's a cool app. But again, it's a monopoly. I generally don't approve of those, especially when they're controlled by the government.

Fraud is a bit of an issue on the app though, so you have to watch out for financial scams.

The Surveillance State?

Charlotte: What was it like living under that kind of surveillance state, a more overt one?

Melanie: Most of the time, it didn't really bother me because I wasn't doing anything wrong. There are privacy concerns with face recognition, but sometimes it can be helpful. For example, I could use it as a key to get into my apartment by showing my face to the screen.

In terms of crime, there was no stealing or violent crime because people knew they would get caught with the cameras everywhere. I allowed my 12-year-old daughter to walk around late at night, although I was cautious. I didn't worry because the punishments were harsh and the chances of getting caught were high. This created a deterrent effect.

However, it was clear that some measures were not enforced against white individuals to avoid drawing attention.

While I believe in privacy, I personally never felt repressed by the surveillance state.

However, I did feel repressed during the COVID-19 restrictions, which led to protests in China.

Pandemic Life?

The pandemic definitely had an impact. We were unable to leave China easily and were essentially stuck there. The situation became more restrictive compared to other countries that were recovering from the pandemic. At that point, leaving Beijing meant facing quarantine upon return, which added to the sense of repression. This experience has influenced my perspective on returning to China, as I have lost some trust and love for the country.

However, this situation brought us closer together as a community, unlike in other places where people were isolated due to the way COVID-19 was managed. China implemented strict measures and closed the country, so while we couldn't leave, we also didn't have COVID-19 cases.

During that time, we only had each other, and I made amazing friends who were fellow trailing spouses. These women had remarkable backgrounds and came from various parts of the world.

Regarding COVID-19, the situation in China was not as extreme as portrayed in the American media. While there were lockdowns in Shanghai and Wuhan, Beijing did not experience such strict measures. We were tested regularly, and anyone entering China had to undergo quarantine. The authorities managed the situation quite well, especially in Beijing, as it is the capital. For the most part, we had very few cases until December of last year when the virus entered Beijing, and many people I knew contracted COVID-19 within a short period.

Prior to that, there was always the possibility of a lockdown if a case was detected in your compound or a friend's compound. However, my apartment complex was never locked down.

We also encountered difficulties when returning to the US. Both times we came back, we had to undergo a two-week quarantine, with the first time requiring an additional week in Shanghai. The second time, we had to quarantine for ten days. Being confined to a hotel room without being able to leave was not enjoyable, but I understand the necessity of containing the virus.

During the pandemic, frequent testing was common, and it didn't bother me to provide swabs and DNA samples since they already had them from when I first arrived. However, when people started getting infected, the test results were not being communicated accurately. My husband and I tested positive for COVID-19, but we never received the official positive test results. It seemed like there was a lack of honesty and transparency. When the government decided to let the virus spread, they didn't inform us, leaving us in the dark. It was frustrating not knowing what was happening and feeling like I missed the final chapter of the journey. It was only through my friends' experiences and the lack of enforced quarantine measures that I pieced together what was going on. This lack of communication and independent discovery of information angered me.

I think because of my background as a biologist, knowing that a pandemic was inevitable, and then experiencing the lack of data and details frustrated me greatly. It may have been the final straw for me because we were already planning to return home after our four-year assignment. When you know you're leaving a place, you tend to focus more on the negatives than the positives. That definitely played a part in my feelings.

However, it was still frustrating, and I can understand what you went through in the States with the fear and anxiety. We didn't have that same level of fear in China. Chinese people had already experienced outbreaks like bird flu and SARS years before.

Some people voluntarily isolated themselves for months in the beginning. I remember riding empty buses when it was usually crowded. Initially, I thought everyone was overreacting, but later, when I returned to the US, I realized the severity of the situation. China had already implemented strict measures, and we were more concerned about someone getting through and potentially not being caught due to the low number of cases in Beijing over the years.

I have a friend who was personally locked down in her apartment for two weeks because she visited a grocery store shortly after a delivery driver who had COVID-19 had been there. The tracking and strict quarantine measures were intense. I wasn't afraid of getting COVID-19 myself, I was concerned about the strict quarantine measures for close contacts and secondary close contacts, as they would be hospitalized.

In general, I believe you had it much worse in the U.S. than I did in China. Just by being back here and hearing people talk about their feelings of isolation and how they held fear in their bodies, I can tell that the experience was much more challenging for you. Especially for younger people, it has significantly impacted how they interact with others and navigate life. The fear of contracting the virus and the potential consequences, such as severe illness or death, was much more intense. In China, while we may have felt confined at times due to restrictions, the containment measures were effective in repressing the virus. The emotional toll and fear you faced were much greater than what I experienced.

Charlotte: I think Americans will be surprised to hear this because we have this impression that everyone in China was wearing hazmat suits and getting their nose swabbed every couple of hours or something extreme like that.

Melanie:

In reality, the nose swabs were only done when traveling out of the country. For regular testing, they used throat swabs, which were less invasive and easier to administer. They had a massive testing infrastructure with tens of thousands of people conducting tests daily.

Charlotte: I don't think Americans would tolerate a city being completely locked down like that and restricting people's ability to leave or enter. It must have been an interesting experience dealing with that.

Melanie:

As to leaving Beijing, yes, we could leave, but there were restrictions on coming back. Especially during the time leading up to the Winter Olympics, Beijing wanted to ensure there were no COVID cases in the city. They made it difficult to return to Beijing after traveling by implementing rules like not allowing entry until you had spent two weeks in an area with no cases.

Even if you went on vacation, you had to be careful because there was a possibility you might not be able to return. You had to be cautious about your cell phone pinging in neighboring provinces while hiking, as it could trigger red flags. Everywhere you went, you had to scan a QR code with your health kit on WeChat to prove your health status. If your cell phone pinged outside of Beijing or in a province with cases, it would show a red warning. It never happened to me or anyone I knew well, but we didn't take the risk and stayed in Beijing. Beijing had plenty of things to do and amazing food, so it wasn't much of a hardship to stay there.

Charlotte: Why do they call the wet markets "wet markets"?

Melanie:

It's because everything is wet. They're always washing it down with hoses, and the stuff is leaking because they're so messy. We had a wet market behind our house. It was a traditional old wet market, but I didn't buy chicken there in the summer because the chicken might have been sitting on that table for who knows how long. However, I never had any health issues or anything buying stuff from there. But those wet markets are almost all gone. In fact, everything like that is gone. When I said that they cleaned up the bathrooms, they also took out the wet markets.

Obviously, they hadn't done that in Wuhan. Although I actually visited the wet market where the virus started, I couldn't go inside, just the outside. It was an indoor market as well. Now, all the wet markets in China are inside and have much better sanitation requirements. Beijing has definitely changed in that regard, but the rest of China has a little bit of catching up to do.

COVspiracies

Charlotte: What was going on in China as far as theories on Covid? In the U.S, we got inundated with different sides of the political spectrum telling us where Covid had come from, whether it was a lab leak, an engineered bio-weapon, or a wet market origin.

Melanie:

China will never admit that it started in China. I have one of my good Chinese friends whose parents, from Wuhan, honestly believe that Americans brought the virus to Wuhan during the military games. And these are educated people who believe this. There's a lot of bad information.

Nobody knows, and China is not going to admit it. So Chinese people are going to think whatever they've heard in their sources of media that they're looking at. I heard everything that you've heard. I was pretty much looking at Western media about it anyway. I was very much subscribed to the idea that there's an animal testing facility near the wet market, which seemed to be the clearest option based on my biological training.

I wish people would just stop blaming anybody for it. It doesn't matter where it started; these things are going to happen, and they're going to start in different places. It's not that place's fault. It is that place's fault if they don't deal with it in an acceptable manner, which may or may not have happened, depending on who you talk to. It is what it is, and we just have to deal with it as a nation, and hopefully as a world. Hopefully, we've learned something.

I'm curious to see if this happens again in my lifetime, which I hope it doesn't, how the world reacts, how China reacts, and how America reacts. I don't know if America will react much differently than it did in the first place, except that people will probably be a lot quicker to put on a mask because I think people kind of got used to that here. Nobody liked it, but at least they got used to it. Chinese people put on their masks pretty fast because they were used to SARS.

In the beginning, there was so much we didn't know, like how it was transmitted. I remember very early on, it was killing men at a much higher rate in China than women. People speculated that the virus had something against men, but the fact of the matter is it's a respiratory disease, and Chinese men almost all smoke, whereas Chinese women don't. So, that put men at a higher risk of dying. As soon as it moved out of China, people stopped that storyline.

It has been interesting to see how the two cultures deal with it for sure.

While I am not a proponent of how China dealt with COVID-19, I also recognize the flaws in how the US handled it. Finding a middle ground in dealing with a virus like this is challenging due to its infectious nature. I can see the freedom the US had, but I also experienced the lack of freedom we had in China. However, it's important to note that we did not have significant COVID-19 cases in Beijing during our time there.

END OF PART 1

To receive Part 2 of this interview where we discuss U.S. and China relations, hugging pandas, and more, make sure you are subscribed to Charlotte Dune’s Lagoon. Part 2 will come out in a few days.

Want to listen to the full interview instead? Check it out here.

Now You

Did anything in this interview surprise you?

Have you traveled to China before?

How was this pandemic experience compared to your own?

![Beijingers walk pet birds to have fun[1]- Chinadaily.com.cn Beijingers walk pet birds to have fun[1]- Chinadaily.com.cn](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!1D4a!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F992a88ba-fd47-43ef-9656-1d0968cd9960_600x405.jpeg)

What a fascinating glimpse of another culture. Love the idea of "bird walks," especially!