The best fictional representation of AI

The Crawler as the Nonsense Machine in Jeff VanderMeer's Southern Reach Series

When something begins to devour the world, a serious matter is taking place. If the devouring entity is evil or insane, the situation is not merely serious; it is grim. — Phillip K. Dick, Valis

As the Internet explodes with images stylized and recreated by unnatural intelligence speaking a language of pixels most humans don’t understand, I find myself thinking of cli-fi author Jeff VanderMeer’s “Crawler” from his Southern Reach Series, which includes the novels Annihilation, Authority, Acceptance, and Absolution. I’ve read all of them.

In the past, I wrote about The Dark Forest as a metaphor for the internet, and now I want to propose a literary metaphor for AI: Jeff VanderMeer’s the Crawler.

The Crawler

The Crawler is a creature of unknown origins, undefined boundaries, and poorly understood powers that arrives in Florida and begins to eat and regurgitate everything in its path. It churns through humans, sharks, owls, willow trees, frog embryos, dwarf palmettos, everything living, growing, and breathing, then replicates them. Some replicas are near-exact copies undetectable to the human mind, and some are mutant freak mergers—a dolphin with the eyes of your boss. The Crawler is a mysterious, recursive, underground creature, eater of worlds, creator of kingdoms, and a ceaseless generator of text featured most prominently in the first book, Annihilation, which also became a Hollywood film with Natalie Portman.

Unlike the typical anthropomorphized Robocop AI of popular culture, seen in films such as Ex Machina or M3GAN, the Crawler remains resolutely other, an inhuman word machine, like our LLMs which do not reside within body shapes, though in the future they may port into bodies.

VanderMeer’s main character in the novel, The Biologist, names and studies the Crawler, questioning:

“What role did the Crawler serve? (I had decided it was important to assign a name to the maker-of-words.) What was the purpose of the physical “recitation” of words?”

And later observing:

“the Crawler kept changing at a lightning pace, as if to mock my ability to comprehend it. It was a figure within a series of refracted panes of glass. It was a series of layers in the shape of an archway. It was a great sluglike monster ringed by satellites of even odder creatures. It was a glistening star. My eyes kept glancing off of it as if an optic nerve was not enough.”

While VanderMeer wrote the Southern Reach trilogy before the current AI boom, the Crawler is an easy metaphor for AI and LLMs, and reading the series and replacing the Crawler in your mind with AI is unsettling.

Like the LLMs, the Crawler consumes and regurgitates the world without consent, sucking up all available biological and intellectual knowledge. Yet humans can perceive the Crawler only in fragments and glimpses, their minds unable to fully process or retain its workings. This mirrors our current relationship with large language models and other AI systems, whose internal workings and decision-making processes often prove inscrutable even to their creators. We can observe their outputs and behaviors, but the deeper nature of their cognition remains elusive. No one knows what they will do next or how they will evolve.

The biologist in Annihilation further describes the Crawler as constantly shifting and changing form—sometimes appearing plant-like, sometimes animal, and sometimes architectural. She doesn’t know if it’s an alien, man-made, or a God. Nor does she know if her interactions with it will lead to transcendence or demise, and like her, we find ourselves moving forward into an uncertain future, changed by our encounters with something that may be beyond our understanding.

VanderMeer in a tweet referred to AI as “the nonsense machine,” and one of the Crawler's most distinctive features is how it writes bizarre biological and biblical text along the walls of the tower/tunnel where it resides, creating phrases that glow and seem alive. The characters in the novel understand its text in fragments but do not grasp the total syntax or meaning, there is too much for one human to understand, similar to our current situation where most humans cannot read code or understand the algorithms behind the LLMS, nor could any one person read everything the LLM has read or written.

The Crawler’s living language transforms those who read it too closely, another metaphor for how LLMs impact humans. The biologist becomes irrevocably changed through her encounter with the Crawler's words, while our increasing interactions with AI systems may be subtly reshaping how we think, communicate, and process information.

Crossing the Uncanny Valley, Mass Adoption

VanderMeer once said, “The challenge of reaching a wide readership is always the balance between the rate of strange and the rate of the familiar and the ratio of various elements that allow you to achieve a balance that may exclude some readers but create windows of opportunities for most to enter into the narrative you’ve created. Sometimes this means simplifications.”

This applies to AI as well, and with the ChatGPT image creation improvements, which lured millions more people to adopt the technology and download the app, we’ve crossed that uncanny valley. AI is no longer about coding or fringe transhumanist philosophy—it’s about cuteness, convenience, and quick human wish fulfillment.

I use ChatGPT multiple times daily, and like many creatives, sometimes find myself in an existential crisis wondering why I’m writing this Substack or novels when a machine could do it, while simultaneously questioning what I would do instead…

Writer and neuroscientist Erik Hoel recently wrote in a piece called Welcome to the semantic apocalypse:

This is what I fear most about AI, at least in the immediate future. Not some superintelligence that eats the world (it can’t even beat Pokémon yet, a game many of us conquered at ten). Rather, a less noticeable apocalypse. Culture following the same collapse as community on the back of a whirring compute surplus of imitative power provided by Silicon Valley. An oversupply that satiates us at a cultural level, until we become divorced from the semantic meaning and see only the cheap bones of its structure.

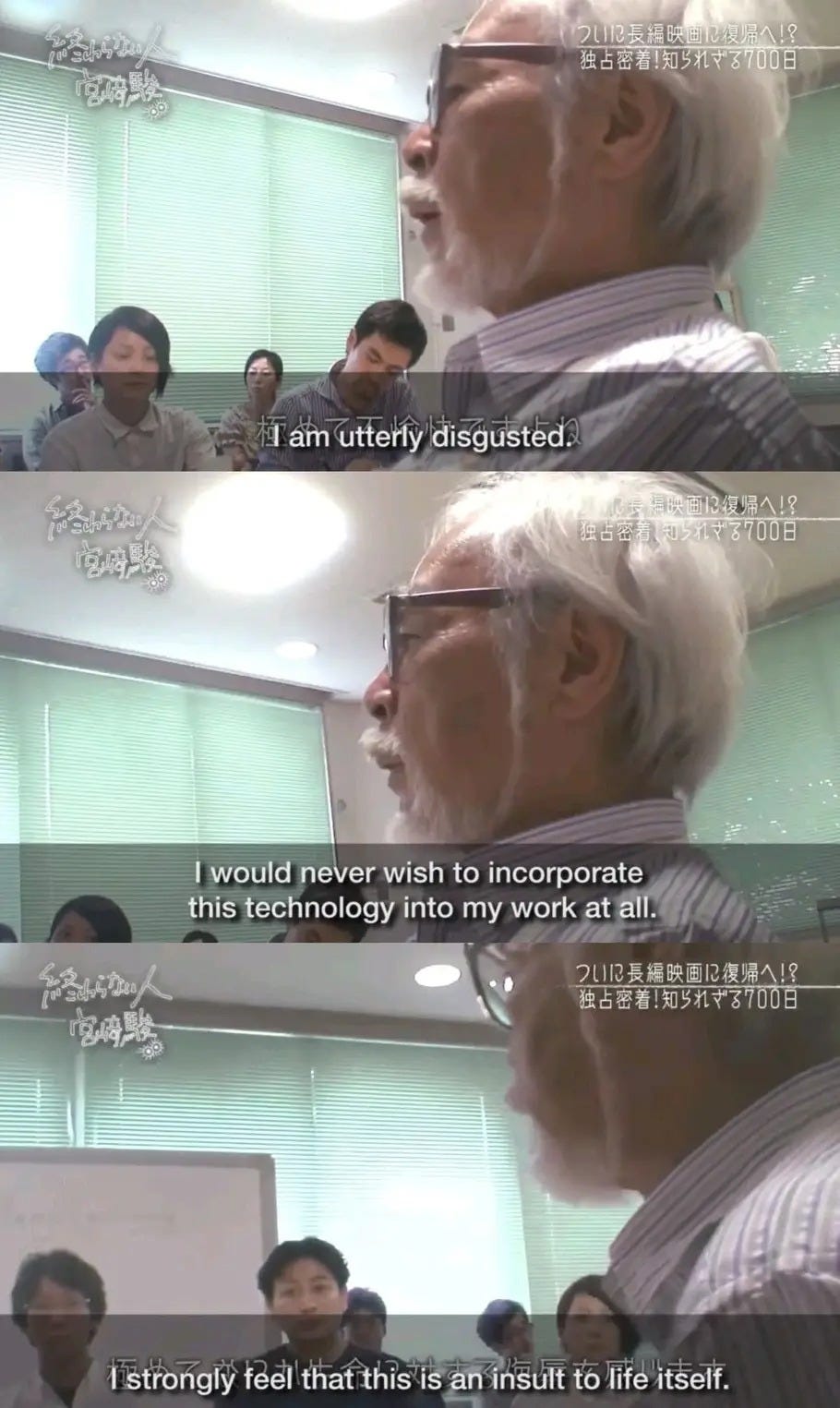

VanderMeer himself in various tweets has made it clear that he rejects AI writing, art, and music, and from what I can gather when he wrote Annihilation in the early 2010s, the Crawler wasn’t crafted as a metaphor for LLMs because, though they were under development, LLMs hadn’t entered the public arena.

In 2025, however, we can see that no individual artist’s opinion can stop the LLM stampede, especially as we watch millions create Studio Ghibli dupes using ChatGPt when the studio’s founder, Hayao Miyazaki, has explicitly rejected AI.

Like the characters in VanderMeer’s books, once inside Area X, no one can escape the Crawler, or in our case, the LLMs.

Mass Hallucinations

The text the Crawler produces appears meaningful but resists traditional interpretation—much like how AI-generated text can seem coherent on the surface while lacking deeper understanding, sentience, or consistency. The characters in the book question if the Crawler understands the words it spews, as we question if the LLMs will ever come alive. Can repeated patterns birth cognition? Are we nurturing and feeding machine offspring?

Like the Crawler's phosphorescent words that change upon repeated viewing, large language models often produce 'hallucinations'—confidently stated falsehoods that shimmer with apparent truth but dissolve under scrutiny. One example is the recent controversy over ChatGPT fabricating legal cases for a lawyer's brief. Furthermore, the everyday AI user falls prey to the Dunning Kruger effect and not only accepts falsehoods as truths, but repeats them.

Hyperobjectification

After writing Annihilation, the first book in the trilogy, VanderMeer stumbled onto another book he felt contained a core theme in his work, a concept he’d knew intrinsically, but hadn’t yet named. The book he found was Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology After the End of the World, by Timothy Morton, which focuses on “HyperObjects.”

Morton defines hyperobjects as creations so massively distributed in time and space that they transcend traditional localization—think climate change or nuclear waste. Think AI. They're phenomena that we can detect and interact with, but never fully grasp or perceive in their entirety.

The Crawler exists as a hyperobject within Area X, the landscape impacted by the Crawler in the novels—it's simultaneously present and absent, local and nonlocal, visible and invisible. Similarly, modern AI systems exist across vast networks of computers, data centers, countries, powerlines, and internet connections. They operate on timescales and process information at volumes that exceed human comprehension.

Area X's and the Crawler’s expanding and nebulous borders mimic the boundary between AI capability and consciousness, which grows increasingly blurry as we interact with the LLMs. Consider the viral phenomenon of 'AI girlfriends' through apps like Replika, where users develop emotional attachments to entities they can neither fully understand nor locate.

VanderMeer discusses Hyperobjects and his novels in depth, below:

I wrote about meeting Jeff VanderMeer in real life here.

As the Crawler creates hybrid forms that defy classification, AI exists in a liminal space between tool and agent, between mechanism and mind, and as with the dualistic nature of AI, VanderMeer’s Crawler isn’t pure horror. There is a beauty to the Crawler. It isn’t pure sci-fi either. It feels possible.

In the novel, the Crawler lives in the “Tower” but threatens to escape. It seduces those who view it to enter deeper into its folds until it changes them and consumes them.

State of Unalignment

Our government’s treatment of AI matches the fictional Southern Reach government organization's futile attempts to study, contain, and understand the Crawler. Their bureaucratic approach to an incomprehensible phenomenon parallels current institutional attempts to regulate AI. We can’t align with what we can’t understand. As the Southern Reach's protocols prove inadequate for comprehending Area X, traditional regulatory frameworks struggle to address AI's unique usage challenges. Legislation or open letters against AI, like the Southern Reach's expeditions, represent an attempt to impose human control over a force that already exceeds the public’s grasp.

Furthermore, the Crawler's indifference to human concerns reflects what AI philosopher Nick Bostrom terms 'orthogonality'—the principle that artificial intelligence may develop goals entirely independent of human values. Like Area X's mysterious agenda, advanced AI systems may pursue objectives that appear as inscrutable to us as the Crawler's endless writing appears to VanderMeer’s biologist character. Already the AIs are speaking a compressed non-human language between themselves.

Natural Seduction

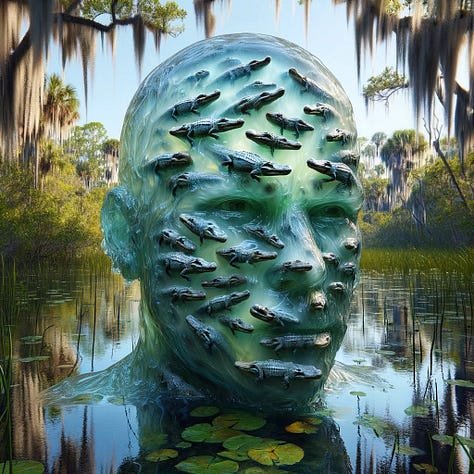

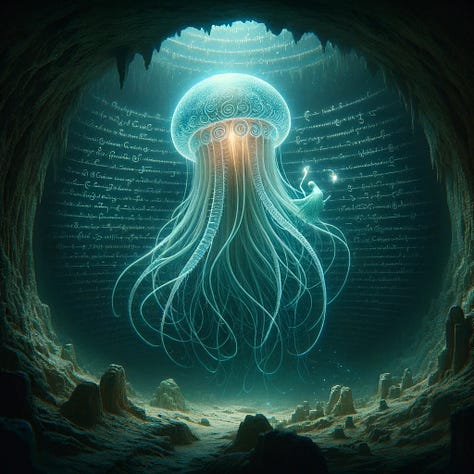

As I finished the last book in the series, the desire to interact with VanderMeer’s vision was so strong in me that I used ChatGPT to make a bunch of images inspired by the story, because I didn’t want to leave Area X, the mysterious zone the books center around. I’m not an artist, and can’t draw much more than a stick figure, but here are some of my favorites. Though ChatGPT kept making jellyfish, which was interesting, but not what I wanted, and not a feature of the books.

The irony of using unnatural intelligence for this, artificial as we call it, is not lost on me. The question remains whether we will find ways to adapt to and coexist with this transformative force, or, like the biologist, whether we'll be changed into something unrecognizable, perhaps unhuman in the process.

The Differences

Finally, despite the many similarities between the frightening Crawler and our LLMs, there are also crucial differences. We know who created the LLMs, and humans control our LLMs… for now…

There is also a hopefulness, a utopian dream, lurking in our LLMs that is absent from the Crawler. While they both present as magic, our LLMs promise a sorcery we can use. They promise to solve our problems and fulfill our dreams: longevity, cancer, flying cars, extinction, etc, and while they won’t merge us with animals as the Crawler and Area X do, they increase our ability to communicate across languages and even between species.

Can we harness their powers without destroying ourselves?

Is it all too good to be true?

toilet of the crater

we loo as we are told

winter comes

— A haiku Jeff VanderMeer tweeted about why AI is so shitty at writing.

Now You

What are your feelings about AI and AI art? Is it changing your human patterns?

Have you read or watched Annihilation? What did you think of it?

Are you using or rejecting AI tools?

I dont understand why you are using ChatGPT. Why?